Ever looked at a social media post and thought it was all a bit TOO complimentary about a certain company or product? Celebrities appearing in TV ads and on posters is nothing new, but when they start promoting products on social media, the lines can become far more blurry.

When posts and articles are clearly labelled as adverts, then it’s all within the law. But a few days ago, the government sent out an open letter to publishers and bloggers reminding them that there are strict rules on this kind of advertising, warning that, “misleading readers or viewers may not only damage your reputation - it also falls foul of consumer protection law.”

iStock

iStock

Who has been in trouble?

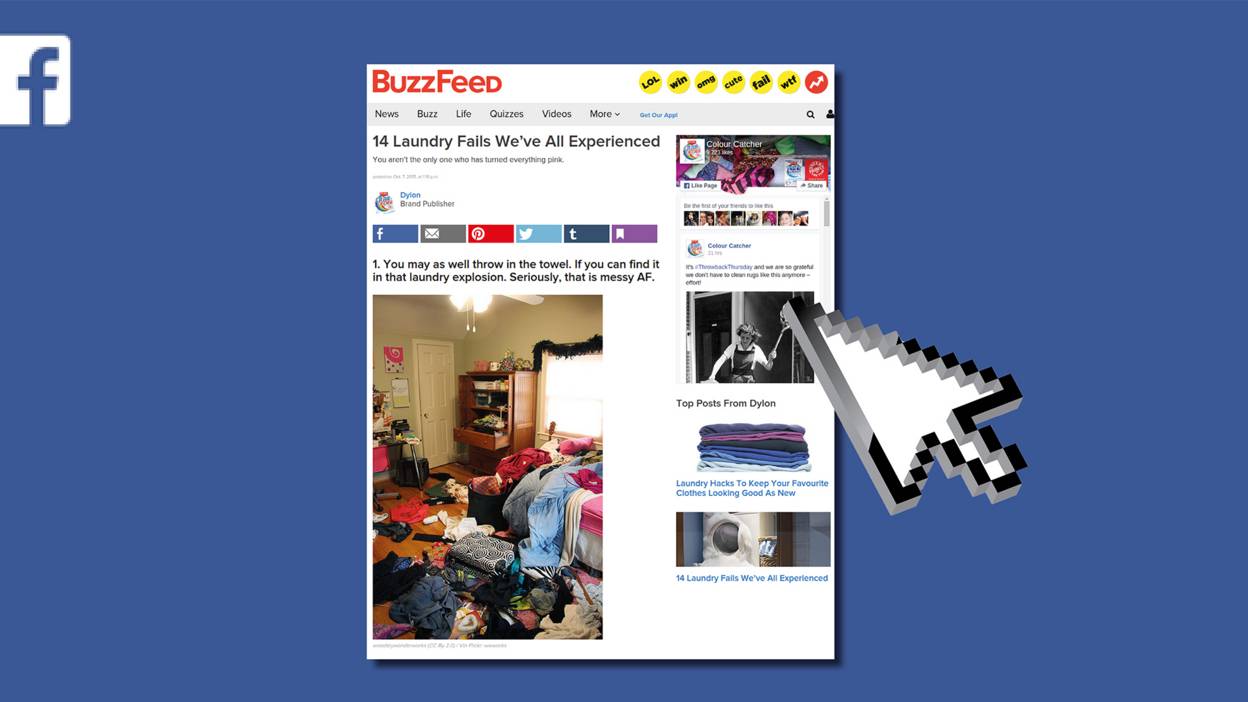

BuzzFeed recently found itself in hot water with the Advertising Standards Authority for its article '14 Laundry Fails We’ve All Experienced', which promoted Dylon. The post was made up of photos and social media posts about laundry disasters. The end of the piece included the line, “It’s at times like these we are thankful that Dylon Colour Catcher is there to save us from ourselves. You lose, little red sock!”

BuzzFeed UK said the lack of ASA rulings about this type of native advertising in the UK meant the company relied on US practices to work out how advertorials are labelled, and that they had used the words 'promoted by' and 'advertiser' next to Dylon on its homepage and search pages.

But the ASA banned it. It said that this explanation was not good enough, because only people who clicked through from BuzzFeed’s home page and search listings would know they were about to view an ad. Anyone who read the page after arriving from elsewhere wouldn’t have known it was an advertisement.

The ASA also rapped Britvic on the knuckles for an advert they ran during a yoga video on Millie Mackintosh’s Instagram page last November, advertising their J20 drinks brand. The ad was banned even though it included a number of branded hashtags as well as #sp within the post, which played out as a loop. Britvic said that it believed it was identifiable as a marketing communication and highlighted that the end frame was branded and included the product name, the #sp hashtag, and the campaign hashtag “#BlendRecommends”, centrally and prominently on the screen.

But the ASA ruling said that many people wouldn’t know that #sp stood for ‘sponsored post’ and was not obvious enough.

And back in 2014, Newsround investigated a number of YouTube stars promoting Oreos, who weren’t clear enough about the fact that they were part of an advertising campaign.

iStock

iStock

What is the law? And what counts as advertising?

It depends who has the final say over what is said or written. For online and social media material to be classed as advertising, there has to be payment and some form of control over what is said by the brand. Payment doesn’t just have to be cold hard cash: freebies count too. If there is no control and the celeb or site can give their honest opinion on a brand or product, then it doesn’t have to be labelled as advertising.

There are no hard and fast rules on exactly how this advertising has to be labelled: it just needs to be very, very clear. Hashtags like #ad help, but as recent rulings have shown, they're not always enough on their own to make it clear that what is and isn't advertising.

The Competition and Markets Authority has warned publishers and bloggers: “Blogs, videos and other online publications influence people’s buying decisions. While paid-for editorial content is perfectly legal, it is important that you are open and honest about it with your audience, so that they do not think they are getting independent information when a business has in fact paid to influence the content. Misleading readers or viewers may not only damage your reputation, it also falls foul of consumer protection law and could result in enforcement by either the CMA or Trading Standards Services, which could lead to civil and/or criminal action.”

How can I spot a sneaky advert?

Buzzfeed

Buzzfeed

- Look out for hashtags. And not just obvious ones like #ad or #spon. Sometimes #samp, #sp and others are used too.

- Consider the language used and the style of post. Is it something that the site or person you’re following would normally post?

- Slogans are a dead giveaway. Would anyone really use meaningless marketing phrases if they weren’t being paid?

Michael Barnett, Print Editor at Marketing Week, explains that we all need to be watchful when looking at brand mentions on social media and websites.

“Social media influencers are without doubt considered by brands to be hugely valuable. They have a great deal of influence over an audience who trusts what they say. If a brand is mentioned on someone’s social media pages, there’s a good chance that there is a relationship there. Think about whether that person you’re following is likely to be endorsing that product without being paid for it. But remember that in general, brands don’t want to trick consumers - they want to be clear too, in order to keep our trust.”

Watchdog and BBC Three are working together. If you have a story about a scam or any other rip off you'd like to shout about, you can contact the producers at Watchdog directly on watchdog@bbc.co.uk and put "BBC Three" in the subject heading.

This article was first published on Wednesday April 13th, 2016