Proud Canaries

Proud Canaries'It's pretty out being out at football'

Meet the grassroots LGBT groups changing the face of football fandom

Five years ago, Jim Dolan was at a West Ham match with his boyfriend and three mates, all season ticket holders and devoted fans, when someone behind them started screaming homophobic abuse at the referee. "I wanted to stand up and say, ‘What's your problem?'" Jim recalls. "If it had been any other part of my life I would have done that, but because it was football it was different."

Frustrated by his failure to speak out, Jim went on Twitter to ask if any other LGBT West Ham fans would be interested in forming a mutual support group. He got positive replies and the Pride of Irons was born. Now, it's been endorsed by West Ham, who say they are "incredibly proud of the strong relationship" they have with the group. "We are determined to lead the way together in promoting and raising the profile of LGBT inclusion within the game," a spokesperson for the club said.

On a warm yet blustery Saturday afternoon, I’ve come to a bar near West Ham's stadium in London's East End to meet some of Pride of Irons' 250 members – a number that includes gay, lesbian, bisexual, straight and transgender fans – who’ve gathered to mark the fifth birthday of the group. Their existence seems to have had a real impact on the club and its fans. Every season Jim and his fellow members, some of whom sit on the newly-formed Official Supporters' Board, give training to stewards on how to help LGBT fans feel safe at matches. And for the past two years, the club's official mascot has joined Pride of Irons for the Pride in London parade.

"We've created an environment where people can come to football and not have to hide that side of themselves," says Jim. "It's not about discussing your sex life, it's about being in a safe space where if those conversations come up you can just talk, and it can be normal. We're West Ham fans first and foremost, it's about supporting each other."

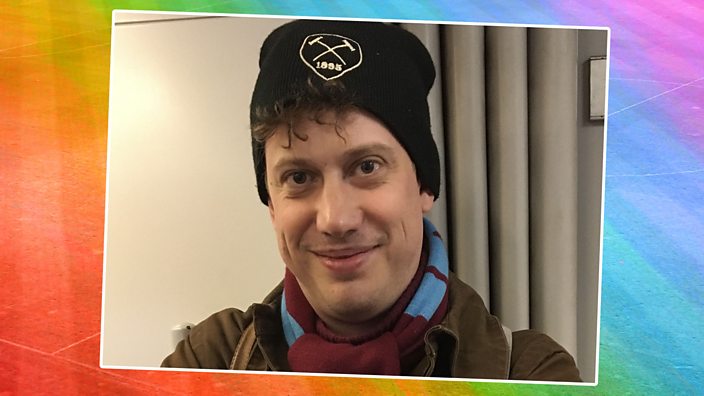

Miles Elliot

Miles ElliotTalking to members of the Pride, I hear stories I can identify with. I was brought up in a West Ham-supporting family, but when I started to question my sexuality as a teenager, I no longer felt like football was for me. My first visit as a teenager to the club's old Upton Park ground was exciting, yet the blizzard of homophobic abuse aimed at opposing players and fans made me feel hurt and confused. The same went for football culture as a whole, including the laddish banter around the English national team. Once it almost went further than verbal abuse – a mate and I nearly got beaten up by two England-shirt wearing fans outside a pub.

For a long time, while I was open about my bisexuality, I stayed in the closet about my support of West Ham. I'd follow the team’s fortunes and watch the odd game, but I still felt that ‘people like me’ would never be welcome in the sport.

Just to be clear I am referring to the men's team rather than women's. In women's football there does appear to be more of an acceptance of both LGBT players and fans alike. In fact, Gilly Flaherty, who is the captain of West Ham United WFC (a team which play in England's top tier) talked about it in the BBC Three documentary Britain's Youngest Football Boss: “We get quite a lot of openly gay football players, but I think we get quite a lot of openly gay female fans as well, it's just seen as like.. it's just very inclusive.”

For me, as a fan of the men's West Ham team, this openness wasn't something I could relate to until very recently. I remember going to the pub in 2012 to watch West Ham win promotion to the Premier League with a 2-1 victory against Blackpool, but still felt afraid that the one bloke screaming that a player was a "lazy poof" might take out his frustration on me.

Luke Turner

Luke TurnerThe statistics seem to back this up. According to figures from anti-discrimination organisation Kick It Out, incidents of homophobic abuse increased 9% from 2017 to 2018, while overall reports of discriminatory abuse in football have risen for the sixth successive year.

Last summer, the charity’s founder, Lord Ouseley, told The Telegraph that homophobia would be "in some ways harder to tackle" than racism in the sport, adding that: "While the growth of LGBT supporters’ groups is a sign of positive progress, we have still not created an environment where LGBT fans and players feel completely welcome in football."

Today, there’s only one out gay male player in a top division anywhere in the world – Collin Martin of Minnesota United in the USA. While in the UK, Liam Davis who plays for Cleethorpes Town is thought to be the most prominent example.

BBC Three / istock

BBC Three / istockFootball's governing body, the FA, is already taking action to tackle homophobia in the sport. A spokesperson said the organisation was "committed to tackling homophobia, biphobia and transphobia in football at every level of the game." They added that the FA is committed to working with partners, like the LGBT fan groups, to "encourage fans and players to report abuse."

Last November, the FA partnered with LGBT charity Stonewall on its annual Rainbow Laces campaign, which sees football clubs across the UK – including all 72 in the English Football League (EFL) – change their corner flags to Pride flags and encourage players and supporters to wear rainbow laces in their boots. Since the 2014-15 season, the EFL has had LGBT inclusion embedded in its code of practice, as well as working with an advisory group – set up in 2018-19 – including Stonewall, Football v Homophobia and Pride in Football.

Meanwhile, there's a growing network of LGBT supporters groups like Pride of Irons within the English and Scottish football leagues. It’s a movement that has ballooned in the six years since Arsenal’s Gay Gooners and Norwich City’s Proud Canaries were formed in 2013 and 2014 respectively.

West Ham United FC

West Ham United FCDi Cunningham of Proud Canaries, who is as forthright and passionate a fan of her club as she is warm-hearted and funny, is also a lead member of Pride in Football, an umbrella organisation that helps 46 affiliated groups with advice and support on anything from diversity training for stewards to how to get a club mascot on local Pride parades. "It's almost in our DNA to be activists," she says. "It's pretty out being out at football."

Nearly everyone I speak to has experienced abuse at matches, from offhand remarks to homophobic chants, outright verbal assaults and even being spat on. Yet their love of the sport has kept them committed to their clubs.

She believes things have changed massively in recent years. The Proud Canaries have an annual parade of their Pride flag around the pitch at Carrow Road. The first year it happened, a fan shouted "don't clap them, shoot them". The incident went viral on fan forums, but the result wasn't an increase in abuse. Instead, fans rallied round – those near the man in the ground complained and many became allies of the Proud Canaries. It’s all part of people "learning what's not OK at football", Di says.

Proud Canaries

Proud CanariesIt’s been a slower process at smaller clubs further down the leagues, however. In Birkenhead, Rover and Out was formed in the summer of 2018 after the explosion of LGBT groups on Twitter inspired Adam Siddorn, a fan of League Two club Tranmere Rovers, to contact the official fan club’s secretary Nina Crombie, whose son is gay, to suggest they set up a group. It hasn’t been an easy ride.

"We're trying to make a difference for a small group of people, but we're seen as the Antichrist," Adam says. "We're on the front line and we're constantly being shot at. You get some idiots who think because you've flagged something up, they're going to do it more. It's like dealing with a child – you tell them not to do it, they'll do it more often – that's what it's like with some of our fans."

Nina agrees that the first months have been tough: "I think it's come too soon for some of our fans," she says. "I feel that there are huge challenges at Tranmere because our fanbase is so small." With an average of 6,500 attending each game, LGBT fans are far more visible. "It's easy for those who are against the group to target us as individuals, whereas at larger clubs people don't get to know who you are."

Nina has faced criticisms of the group first-hand both online and in person. She was recently out in town with her son when a Tranmere fan came up to them and let loose about the LGBT group. "My son is very proud to be gay but wasn’t comfortable talking to this person – he just went into his shell. I will come out fighting, but it’s hard for him."

Rover & Out / Gay Gooners / istock

Rover & Out / Gay Gooners / istockAccording to Adam, the presence of the group's Pride flag within the Prenton Park ground hasn't gone down well with some older fans. "Some confronted stewards and said 'we're not here to look at that type of flag,'" he claims.

There's still a lot of wariness among Tranmere’s LGBT community - social media support for Rover and Out often doesn't translate into a visible presence at matches. "They still don't want to be seen because of the way our fans are, sadly," Adam believes. Nevertheless, he feels confident that things will change in time. Nina says she’s already seen their work have a positive impact – an older trans woman who had recently transitioned told her that she had worried that she would no longer be welcome at matches, but now, thanks to the group, she feels safe to return.

Tranmere Rovers told BBC Three they have "no records" of anyone reporting homophobic abuse from fans, and that measures have been in place for many years to protect their supporters from abuse. "The club works in close connection with all our fan groups to encourage all supporters to feel welcome at Prenton Park," said a spokesperson. "We have recently hosted a successful welcome evening with Rover and Out with two of our first team players and our senior club representative, who is also our diversity officer."

Proud Canaries

Proud CanariesPride in Football’s Di Cunningham believes that grassroots work done by supporters groups has a better chance of ending prejudice in the sport, and among fans, than any top-down initiative from football’s governing bodies.

She and Pride of Irons’ Jim Dolan have praise for Leeds United, who signed a best-practice agreement with their LGBT supporters group, Marching Out Together, back in February. They hope it will become standard across the sport, but Di believes that’s only one element of progress. "Regulation is important but actually what shifts things is fans changing their own attitudes," she says. "They don't want a bossy corporate sign telling them what to do, but if another fan turns around and says 'we don't say that here', it's much more powerful."

As part of their mission to advocate for LGBT football supporters and build a rapport with all fans, Pride of Irons welcomes straight members because "otherwise you're just speaking to an echo chamber". Jim, and all of the groups I speak to, have a similarly nuanced view on the appropriate action clubs should take when homophobic, transphobic or biphobic abuse is encountered at matches. Banning people from grounds, Jim claims, merely takes the hate out of the stadium and onto social media, and will never change attitudes. Everyone I speak to is united in believing that banning should only be used as the last resort, and that calling out abuse and education is the way to bring about change.

Joe White of Arsenal’s Gay Gooners and England’s LGBT supporters group Three Lions Pride agrees. "If you're safe to do so, challenge behaviour, because having those conversations is more powerful than slapping a ban on someone who then goes 'it was the gays that got me banned' – that can make them worse,'" he says. "Nobody wants to see fans being banned if there's a way to educate and make sure this doesn't happen."

3 Lions Pride

3 Lions PrideLGBT England football fans were faced with a similarly difficult decision during the 2018 World Cup held in Russia. Do they go and support their team, or boycott a tournament in a country notorious for its hard-line stance on gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people? A small group including Di and Joe decided to face their fears and make the trip.

"We decided the best thing we could do was go out there and be seen," says Joe. "It was easier for us to be visible as foreign fans, with the protection of FIFA, than it would be for Russians, so they couldn't ignore the fact that LGBT fans existed and were there, out and proud."

Di was questioned about her pride flag when she entered the stadium in Volgograd for England’s game against Tunisia, but was able to unfurl it in the stadium, as a protest against FIFA's decision to allow Egypt's team to be based in Chechnya, where LGBT people are allegedly being incarcerated and killed by the pro-Kremlin regime.

As a result, they and many of the UK groups are now raising money to fund safe housing or an escape route for at-risk LGBT Chechens, and to raise awareness of this issue. Di sees this as an example of how the work of Pride in Football can have an impact far beyond individual clubs. "Football has this amazing power to influence change, and we should harness that," she says.

3 Lions Pride

3 Lions PrideOutside the London Stadium after the final whistle of West Ham’s 2-0 victory over Newcastle back in March, the Pride of Irons regroup around a beer stall where a DJ blasts Queen's classic hit Don't Stop Me Now. Thanks to the victory and the emotional renaming of a stand devoted to club legend Billy Bonds, everyone is in high spirits – there’s just the same ribbing humour and match analysis as you’d get with any other football fans. Someone returns from the hotdog stall with two sausages and with a cheeky smile says, "it’s been a while since I’ve had more than one at once".

The last track of the evening is I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles, West Ham's club anthem of joy and failure. As it blasts out, the happy, drunken fans of the Pride of Irons – straight members among them – sing along, arms raised and united with everyone else. It’s an emotional moment as I feel like I have finally found my people.

"I've seen other fans change," says Jim. "They’ve gone from seeing us just as lesbians, gay, bisexual or transgender people, to seeing the difficulties we go through, what we're trying to achieve and the benefits of making that happen. I'm glad we're making a difference and hope we can keep doing that until we're not needed anymore."

For information and support on LGBTQI+ issues, these organisations can help.

Originally published 10 May 2019.