BBC Three / istock

BBC Three / istockWhy was everyone talking about emotional labour in 2018?

You've probably seen this buzzphrase doing the rounds

In 1991, Mariah Carey famously sang “you've got me feeling emotions” - but maybe the 2018 version should be, “you got me performing emotional labour”?

OK, maybe it's not as catchy as another Mariah classic that's on repeat in every. single. shop. at the moment (All I Want For Christmas, obvs), but 'emotional labour' is a buzzphrase that you are likely to have come across. Although it's been doing the rounds on Twitter for a while, more recently it's been talked about in mainstream newspapers and magazines, and has become a water cooler topic at work.

But... what is it?

Emotional labour means many things to many people. But, put simply, it's when someone feels the need to suppress their own emotions.

The term was first used in 1983, when American sociologist Arlie Hochschild wrote about it in her book, The Managed Heart. At the time, Arlie described emotional labour as having to “induce or suppress feeling in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others”.

In other words, having to keep a fake smile on your face all day - often because you work in a service industry job - regardless of how you're really feeling, because customers, and your boss, might complain if you're anything less than wildly cheery.

But the phrase has more recently been popularised by US journalist Gemma Hartley, who used the term in a different way in a 2017 Harper’s Bazaar article titled 'Women aren't nags - we're just fed up'. In this, she links emotional labour to housework and 'life admin'.

BBC Three / iStock

BBC Three / iStockWhen Gemma’s article was first published just over a year ago, it struck a chord because she wrote about a specific kind of frustration felt when this life admin - and all the research and thankless 'nagging' required to keep on top of it - builds up.

That includes making travel arrangements, going food shopping, or simply reminding partners or housemates to buy loo roll because, well, some people are so lazy they’d rather use the cardboard cylinder the toilet roll was once wrapped around than go out and buy a new pack. (Gross)

All of this leaves you feeling tired, grumpy and over-stretched - and Gemma says this exhaustion is why emotional labour is so… well, emotional.

At the same time, though, the term has taken on another, heavier meaning - one that's specific to marginalised people.

In this case, it's the more insidious, wearying work of having to pretend you're not as bothered by microaggressions in the workplace as you really are - whether those aggressions are racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist... any situation where you feel like you've been stereotyped, or your identity has been attacked in some way, and you have to pretend that it's fine. More on this later.

So it's not about housework...?

This is the source of some contention.

In a recent interview, Arlie Hochschild said she was “horrified” by some people’s housework-focused and woman-centred interpretation of the term.

Emotional labour, Arlie believes, is simply about performing or deliberately obscuring emotions at work. Everyone from the man who has to pretend some mean, even bigoted 'banter' from a colleague hasn't hit a nerve, to the club bouncer who has to act tough even though he's feeling sad, is undertaking emotional labour.

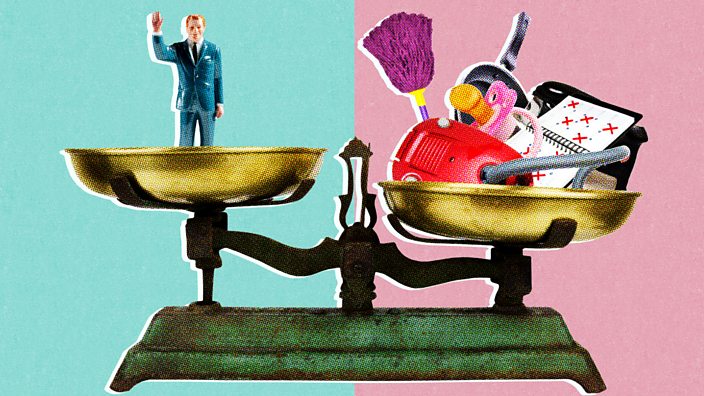

But others argue that emotional labour in the home is pervasive, and that it can often be gendered. In a 2016 study, for example, it was found that, when it comes to cooking, childcare and housework, women in the UK are responsible for 60% more unpaid work than men. This isn't just the odd bit of work here and there: across Britain, recent data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that people do more than a trillion pounds worth of unpaid housework every year.

BBC Three / iStock

BBC Three / iStockIn her book, Work Like A Woman, a manifesto to improve the UK's work-life balance, retail expert and broadcaster Mary Portas refers to this as “the mental load” - and claims that it’s particularly bad for women.

She tells BBC Three that “there’s no difference” between the mental load and emotional labour, as both refer to “how much [women] pick up that we don’t realise”.

“Girls in their twenties instinctively and mindlessly - not mindfully - pick this stuff up,” she says. “It’s exhausting and, as you get older, it goes to caring for children, parents, it takes up a huge part of life.”

Does putting on a 'happy face' also count as emotional labour?

Absolutely - but this covers a lot of ground.

If you're a barista working in a cafe, for example, your emotional labour involves wearing a big grin for customers for the entire duration of your shift, even if you're having a terrible day.

Novelist and columnist Stephen Marche, who co-wrote (with his wife Sarah Fulford) the book, The Unmade Bed: The Messy Truth About Men and Women in the 21st Century, tells BBC Three that this is why emotional labour “isn’t explicitly gendered” - because male workers have to perform emotional labour too.

“For a [male] cabbie, every time a drunk gets into his cab [he] performs emotional labour" by having to talk to and humour them, he explains.

But on the other end of the spectrum is the extra emotional labour you shoulder if you're a person of colour, a LGBTQ+ person, or a person with a disability. That's the emotional labour you're expected to perform at work on a daily basis, pretty much every time you're faced with uncomfortable or offensive situations - which is, unsurprisingly, quite often. Plus, there is the added expectation that you will repeatedly, yet politely, correct and 'teach' the offending colleague.

Writing in Gal-Dem about how this affects women of colour specifically, writer and poet Sam Siva explains: "Women of colour are not just exploited by capitalism in demanding and low-paid work, but also through the requirement to perform heavy emotional labour.

"We police our language and behaviour, we take on roles of healing when supporting each other, and we carry the burden of educating in order to 'teach' or 'explain' what microaggressions are."

For example, it’s well known that many black women feel the need to suppress true feelings, for fear of being seen as the “angry black woman” stereotype.

BBC Three / istock

BBC Three / istockCarys Afoko, executive director of feminist organisation Level Up, explains to BBC Three: “Being a black woman means that emotional labour is expected of you in most situations, and also that you need to subdue your own emotions for fear of being read as aggressive or weak, or ‘crazy’.”

Case in point: tennis superstar Serena Williams. She was upset with an umpire and called him a “thief” for docking her points at the US Open earlier this year - something she said would never happen to a man who said worse. It was a cathartic moment for many black women, who took to social media to share examples of the times “they [had also] felt the need to stifle their anger in the workplace, or retype emails out of fear of sounding too combative”.

But this is a weariness felt among many minorities. One woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, tells BBC Three that she faced casual homophobia when telling colleagues that she was expecting a child with her same-sex partner - and was expected not to be bothered by it.

"When people discovered my partner and I were expecting a child, the first response I got from three colleagues - including someone in a managerial position - was, 'How did you do it?'" she says.

"As if the first thing you'd say to a straight person would be, 'Oh, that's great news, what sex position did you use to get pregnant?'

"The first time, out of a weird sense of politeness, I answered the question. Not only was that uncomfortable for me at the time, but it's the emotional labour I felt after that was harder. Why had I 'given in?' Why did someone I didn't know particularly well now know more about a [personal] situation than people I'm far closer to?

"Basically, why wasn't I strong enough to stand up for myself and just politely but firmly say, 'This isn't an appropriate question'?"

So 'emotional labour' can mean lots of different things?

Pretty much.

The term “emotional labour” is working a double shift right now. At times, according to Gemma's definition, it refers to the thankless scrubbing, mopping and other Cinderella-y stuff that often falls to women - along with the admin that goes with it.

But at other times, it’s the requirement for people - all people - to change their emotions to suit others at work, including the burden of having to put a brave face on it when someone you work with has hurt you deeply with their own prejudices.

However, some people feel like the term 'emotional labour' is being too readily applied to things that don't really qualify.

In her Slate article titled 'Please stop calling everything that frustrates you emotional labour', Haley Swenson writes that the phrase is "used and abused as a catchall for what are either pretty complex, sticky situations or just straightforward cases of male helplessness".

She adds: "In our rush to bring greater awareness to gender frustrations that we’re just beginning to talk about publicly, we should remember that not all kinds of gender and relationship problems are in fact, emotional labour."

Hopefully, though, giving this phenomenon a name will cause something to change - because frankly, keeping a big fake smile on your face all day, through pain, sadness and frustration, is, for many, just exhausting.