It started around Christmas. I was thinking about stuff to buy my girlfriend, who’d said she wanted a “cool” parka. I saw one in the shops with a red fur trim and floral embroidery, but I wasn’t too sure. So I asked her –would she like this parka? The next day, an advert popped up in the sidebar of my Facebook. It was the exact same parka I’d described to my girlfriend. I was freaked out.

The more I asked around, the more similar stories I heard. One acquaintance told me about visiting his friend, Dave, in Dorset. They went for a walk (alone) and Dave told him about a specific watch he wanted to buy. My acquaintance had never even heard of this brand before. But, the next day, he saw ads for that same watch on his Facebook account.

Another told me she’d been watching the courtroom episode of Apple Tree Yard, in which Mark Costley’s name is repeated numerous times. Shortly afterward, Facebook suggested a friend with that name – a complete random who she’s never met and with whom she shared no mutual friends.

Last year, the American news outlet, nbc4i, ran an experiment to test whether Facebook was listening to them. They recruited Kelli Burns, professor of mass communications at the University of South Florida. Burns enabled the microphone feature in her Facebook app and said aloud to the phone, “I’m really interested in going on an African safari. I think it’d be wonderful to ride in one of those jeeps.”

BBC Three

BBC Three

Less than a minute later, a safari story appeared in her Facebook feed.

The experiment made global headlines.

But Professor Burns has since told the BBC that the story got "blown out of proportion". She’s heard from a lot of other people sharing similar stories.

But, she said, "I believe there are a lot of strange circumstances and coincidences out there."

I decided to try my own experiment. The Pen Test Partners are a cyber security company who test software and products to see how secure they are. David Lodge is one of the testers. On his advice, I obtained an unused smartphone with clean sim.

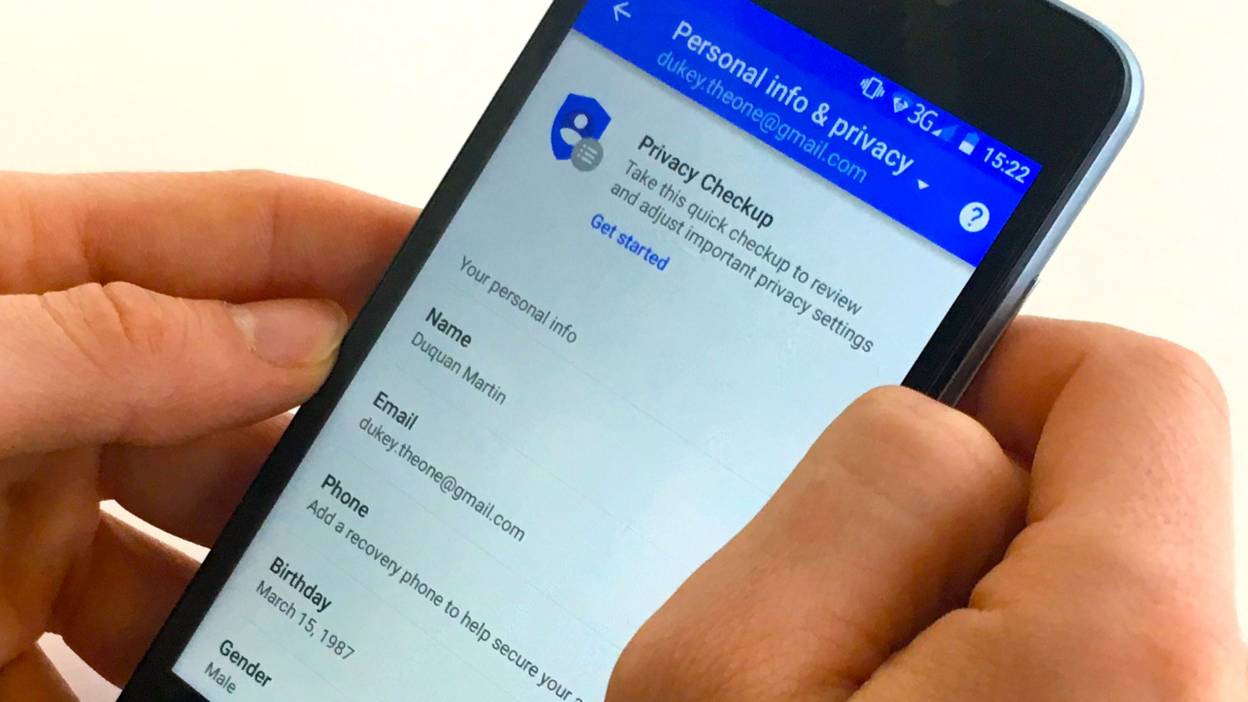

Then I set up some new profiles, so that nothing from my existing profiles or previous search history would influence the experiment. When I was a teen, me and my mates would make up fake names to introduce ourselves with on nights out. They had to be quite unlikely. My favourite was Duquan. Now, Duquan Martin’s gmail and Facebook accounts were born.

I enabled the microphone in all the apps and then started talking jibber jabber to the device (in private – obviously – and away from interfering noise).

BBC Three

BBC Three

First, I repeated the thing with the parka. This time, nothing happened in Facebook. But, in Google, the top image that appeared when I searched for 'Ladies parka' after chatting away about red fur trim matched the description. 'I’ve cracked this already', I thought.

But the same parka appeared when I searched on my iPhone and mac – devices that hadn’t 'heard' my earlier chatter.

I tried something else.

“I would like a parrot drone. Parrot drone. Parrot. Drone.”

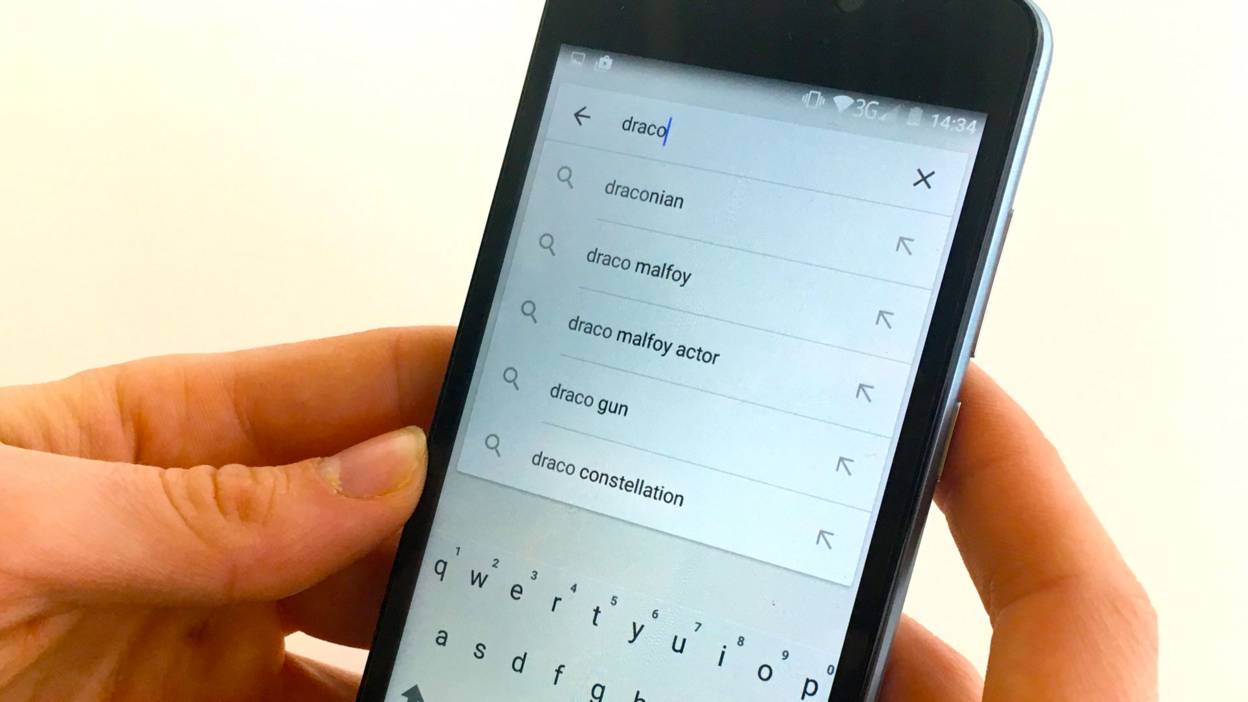

Sure enough, once I started typing ‘parr’ into Google search afterwards, “parrot drone” came up as the second highest search term.

But it’s a popular gadget. I decided to get more obscure. Dracola was a cola product made for 'Halloween fans of all ages' by Transylvania Imports. Ages and ages of jabbering on to my smartphone about this soft drink yielded nothing.

I also tried talking about huskies, garden gnomes and adult diapers. (The last two were suggested by this reddit thread, full of other people discussing whether their phones are listening to them). Nothing.

Last summer, Facebook issued a statement.

"Some recent articles have suggested that we must be listening to people's conversations in order to show them relevant ads. This is not true," the company said.

BBC Three

BBC Three

As for Google, Emily Clarke, a spokesperson from the company, told me that they do not collect data from your microphone, unless you’re using the “OK Google”, voice-recognition function. In their privacy policy, it clearly states, “We do not sell your personal information to anyone”. They do explain how they use data to inform ads, “We try to show you useful ads by using data collected from your devices, including your searches and location, websites and apps you have used, videos and ads you have seen, and personal information you have given us, such as your age range, gender, and topics of interest.”

They also have terms for app developers, which state, “The privacy policy must, together with any in-app disclosures, comprehensively disclose how your app collects, uses and shares user data, including the types of parties with whom it’s shared.”

BBC Three

BBC Three

Does that mean that all this anecdotal evidence is, as Prof. Kelli Burns suggested, just “coincidence”?

David Lodge and Ken Munro, of Pen Test Partners, ran an experiment themselves last year to show how this technology could work. They created an app, gave it access to the microphone and began chatting near the device.

"We set up a listening server on the internet,” said Ken. Everything that microphone heard on that phone would go to that server, in real time. Anyone with access to that server – in this case, it was just David and Ken – could hear the voice data.

So they demonstrated that it’s perfectly possible for this to happen, at least from a technological point of view.

Patrick Wardle is a former NSA and NASA employee, who now works as Director of Research at Synack, a cyber security company. In his free time, he develops free Mac security tools for fun.

One of these tools is “Oversight”. It notifies you every time an app is attempting to access your machine’s webcam or microphone.

I asked him if he thought apps like Facebook, Google, Instagram are snooping through your mic.

“I would be very surprised,” he told me. “They’d get so much bad press. But I do think there’s a danger that smaller, third-party apps could be doing this.”

Patrick told me about a case involving the app for the Golden State Warriors – a professional basketball team from Oakland, California.

BBC Three

BBC Three

According to a federal lawsuit, the app “continuously listens in on users' private conversations, without permission”.

Signal 360 licence the technology for the app. Lauren Cooley, their Chief Operating Officer, said in a statement, "Our technology does not intercept, store, transmit, or otherwise use any oral content for any purpose. We do not capture or store any conversations."

The case is still ongoing.

One of Patrick’s Oversight users found that, when they toggled “off” in the Mac OS Shazam app, the app stopped processing data - but recording continued.

Patrick doesn’t believe that Shazam were collecting data for malicious purposes. But they were still collecting it.

Patrick contacted Shazam and they replied “we use this continued recording on iOs for performance, allowing us to deliver faster song matches to users”.

James A. Pearson, VP Global Communications, Shazam, reassured Patrick that they would update their Mac app.

BBC Three

BBC Three

“The problem is that we don’t know which apps use the microphone data legitimately,” Patrick told me. “We have no guarantee.”

It’s not just our phones. In 2015, The Daily Beast ran a story suggesting that Samsung Smart TVs may be listening to you.

Samsung’s privacy policy reads, “Please be aware that if your spoken words include personal or other sensitive information, that information will be among the data captured and transmitted to a third party.”

Samsung later clarified that they did not retain or sell this audio data – but confirmed that "If a consumer consents and uses the voice recognition feature, voice data is provided to a third party [..] At that time, the voice data is sent to a server.”

Plus, there's always the danger that someone could hack into your microphone or webcam. Patrick told me that "basically every system is hackable". There are numerous cases of individuals hacking into users' webcams in a malicious way.

BBC Three

BBC Three

When it comes to your phone, Patrick points out an important difference between iOs and Android.

“On iOs, an application has to explicitly request access to the microphone, which the user has to explicitly deny or allow. On Android, it’s a little different. On installation, the app will ask for various permissions all at once. I think a lot of people just click ‘allow’ without reading,” he said.

Patrick advised, “When an application wants permission to use your microphone, you’ll often get a pop-up - pay attention to that! If it makes sense to use the microphone – like you’re making a call or something – that’s fine. If it seems weird, click ‘no’”.

It’s easy to switch off your mic altogether in any apps you’re worried about. On an iPhone, head to the app’s settings, select privacy and slide the microphone to “off”; on Android, head to settings and then privacy, and change the permissions the app is given.

So, basically, yeah, lots of apps may be listening to us. If you have apps on your phone that use the mic, unless you switch that off, or explicity disallow those apps from accessing your mic - your phone will be listening! It's been proven that the technology can do that. That's not to say that they're using that information to serve adds, but it's potentially worrying. In the meantime, if anyone is stuck for ideas around my birthday, I've basically given you a gift list above (no, not the adult diapers).

BBC Three

BBC Three